Completed Clean Harbour Projects

Clean Harbour Program Successes

As the Hamilton community works to achieve the goal of delisting Hamilton Harbour as an area of concern (AOC), it is important to recognize and celebrate the projects that are already complete and having an impact on the harbour and its surrounding communities.

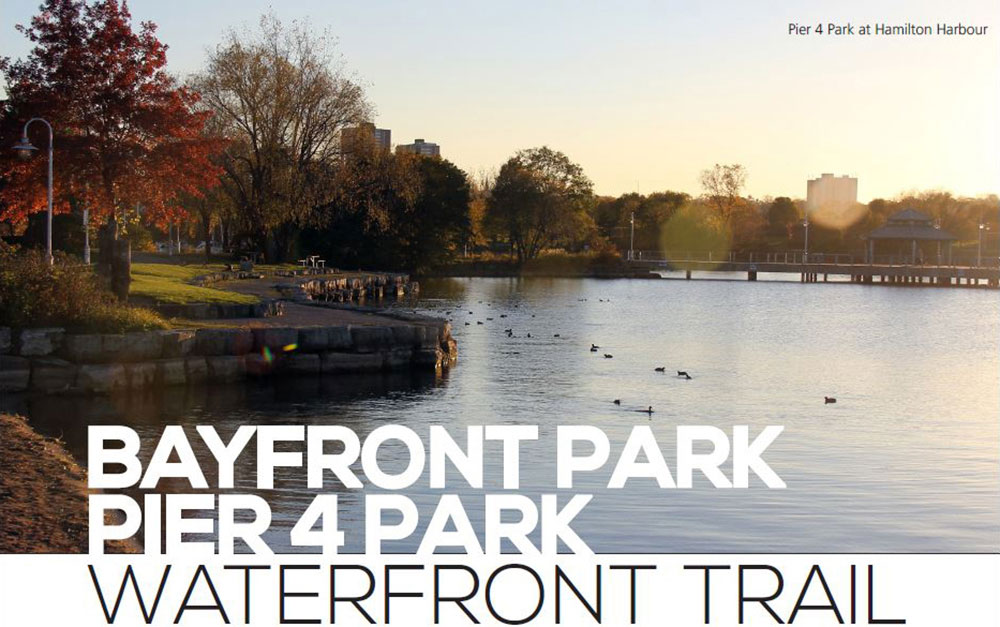

Bayfront Park, Pier 4 Park and the waterfront trail are examples of the innovative and dedicated work of the City of Hamilton and its partners, to transform an unappealing industrial landfill site into a beautiful recreational public space. Once filled with hazardous waste, the shoreline of Hamilton Harbour was converted into a serene park offering residents a place to walk, bike and take a moment for quiet reflection.

At the time of the park opening in 1993, the highly complex development project received numerous design awards at the local, national and international level.

Other elements to the project included installation of an armour stone shoreline enhancement, preservation of an ecologically sensitive wetland, creation of a fish habitat, relocation and restoration of a heritage building and reclamation and renovation of an 80-foot tugboat to serve as a water play area.

The remediation plan and processes later served as a model for other municipalities that faced the same drastic, environmental challenges.

Bayfront Park transformed from landfill to park

Bayfront Park is 40 acres of land with approximately 25 acres of it formed by landfill in the early 1960s. The site was owned by the Lax brothers and was known as the Lax property which was a landfill comprised of industrial waste and rubble. As a result of the contamination, the City of Hamilton had to deal with all the hazardous materials on the site. A remediation plan was developed and approved by the Ministry of the Environment.

The City of Hamilton removed approximately 20,000 tonnes of industrial waste and contaminated soil.

Hamilton then protected the shoreline from erosion and created a fish habitat with the placement of armour stone along the water’s edge. Along with replacing the soil, native trees and shrubs were planted to enhance the park.

Bayfront Park has had to contend with waterfowl and E. coli contamination issues. In an effort to restore the beach’s intended use for recreation, the City of Hamilton needed to address the bird problem. To stop the birds from inhabiting and polluting the park, the City planted bushes above the beach along the path’s edge. The bushes were planted as a deterrent. The concept for this is that if a bird can’t visually see potential dangers ahead, it will not go beyond a given point. Visual deterrents are a common technique often used in waterfowl management of this type.

Pier 4 Park providing swimming and recreational activities

With a small, man-made beach on Hamilton Harbour, Pier 4 Park offers residents a recreational public space that is surrounded by grass with nearby bicycle and walking paths. Before 2005, the area was severely challenged by E. coli. This meant that the beach was closed for half of the summer swimming season. The E. coli levels were well above the provincial safe swimming guideline of 100 colony forming units of E. coli/100 ml of water.

The City of Hamilton and Environment Canada came together to find out the source of the E. coli. In 2005, Environment Canada, using a genetic investigative approach called microbial source tracking, confirmed that feces from geese, gulls and ducks was the most likely source of E. coli at Pier 4 Park. Water fowl management, in order to control the E.coli, focused on bird deterrent mechanisms. This included oiling of eggs, street sweeping of paved walkways, dog walking patrols, the installation of visual and moving features such as artificial hawks and the periodic use of lasers to disturb the environment.

In August 2005, the City of Hamilton installed a fence and vegetation barrier around the perimeter of Pier 4 Park and a row of buoys parallel to the beach offshore, thereby preventing the birds from accessing the beach from the walkway or the water. The City also maintained the beach sand by having city workers rake the sand by hand to remove debris. In recent years, other environmental challenges have arisen.

Tug boat playground at Pier 4 Park

The presence of microcystin, a hepatotoxin released by cyanobacteria harmful algal blooms (cHABs) have been responsible for beach closing. This continues to be a big environmental challenge because, at present, there are no means for the City of Hamilton to control or prevent cHABs accumulation in the nearshore area of the beach. This is a harbour-wide issue and is being addressed through the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan by the implementation of phosphorus reduction strategies.

Today, residents are able to enjoy a park at the water’s edge through the on-going efforts of the City of Hamilton and its community organizations.

Waterfront Trail among native plants and fish habitat

Hamilton’s Waterfront Trail, along the shoreline of Hamilton Harbour, was designed by biologists to encourage the growth of self-sustaining fish and wildlife along with the beauty of native plants. The trails provide residents with a multi-use path for walking, cycling and accommodating wheelchairs so the park can be enjoyed by all. The goal of the trails was to allow residents to be in touch with nature and experience it. The natural restoration of the shoreline as well as the selection of native plants allows residents a chance to be close to nature. The trail meanders along the water’s edge from Bayfront Park to the nature sanctuary at Cootes Paradise.

How does it relate to the Clean Harbour Program?

The parks and shoreline along Hamilton Harbour are very much part of the overarching mandate set out in the Clean Harbour Program to revitalize and protect the harbour from further environmental damage. While the Clean Harbour Program is a series of very specific projects aimed at reversing environmental damage to the harbour, increasing recreational opportunities and park development are both part of the overall ‘big picture’ of environmental success for this location.

How does it relate to the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan?

Waterfront Trail along Hamilton Harbour

Hamilton Harbour is among 43 Areas of Concern within the Great Lakes Basin by the International Joint Commission for Canadian-American Boundary Waters in 1985.

Given this concern, the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan committee researched the issue of access to the shoreline in the city.

Previous to 1990, It was determined that less than five per cent of the City of Hamilton’s shoreline was accessible to the public. With the financial and leadership support by the City of Hamilton and other key stakeholders, Pier 4 Park, Bayfront Park and neighbouring trails changed all this by allowing residents access to Hamilton Harbour and its shoreline.

Support from various stakeholders and the City of Hamilton led to a number of successful remediation projects including Pier 4 Park which opened in 1993. One of the key elements of the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan is the reduction of phosphorus flowing into the harbour through wastewater and storm water. Phosphorus is one of the elements that lead to the presence of microcystin, a hepatotoxin released by cyanobacteria, creating harmful algal blooms (cHABs) that have been responsible for beach closings.

Historic Gartshore Thomson building at Pier 4 Park

The Gartshore-Thomson building was donated to the city by the Fracassi family and was moved to its present location at Pier 4 Park in 1992. In the early 1900s, the Gartshore-Thomson Pipe and Foundry Company was one of Hamilton’s leading industries as the largest pipe manufacturer in the country. The company was recognized across Canada for its high quality cast iron water and gas pipes.

It was established in 1870 by Alexander Gartshore, who was the son of John Gartshore of the Gartshore foundry in Dundas. The Gartshore Foundry in Dundas is where, in 1859, the engines that powered the pumps of Hamilton’s original water system were built.

In fact, in 1933 it claimed to be the only manufacturer of band spun cast iron pipe, which was a technically superior type forged centrifugally in sand lined moulds.

Gartshore building at Pier 4 Park

The company was bought out in the 1940s by Canada Iron Foundries. It operated as a foundry until the mid-1980s. The designated historical building was restored and preserved and now provides meeting space and washrooms at Pier 4 Park.

What is the return-on-investment for the residents of Hamilton?

For the residents, an accessible waterfront and harbour is the ultimate achievement. By transforming this former landfill to public parks and trails, residents are given more recreational opportunities and a chance to enjoy their waterfront around the year.

Some of Hamilton’s most attractive public spaces are its waterfronts and beaches. For this reason, maintaining, protecting and enhancing its public spaces are key initiatives for the City. In order to continue to enjoy Hamilton Harbour, we must protect its water. To preserve Hamilton water quality, the amount of E. coli entering the harbour, as a result from geese and other birds, must be limited and managed.

There are a number of ways that Hamilton is focusing on these initiatives. The control of bird populations is a significant challenge. Birds are discouraged from inhabiting the beach through pyrotechnics, laser lights and bird of prey flags. By grooming and cleaning Hamilton’s beaches and pathways, bird feces are kept to a minimum. Hamilton aims to encourage desirable bird populations, such as terns, to nest and grow in Windermere West. The focus on monitoring bird populations ensures that Hamilton residents can enjoy the parks neighbouring its harbour.

How does it related to the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan (HHRAP)?

The goal of the project is to limit the amount of E. coli that enters the harbour as a result of geese and other birds’ feces. Two components that contribute to the delisting of the harbour are clean water and making the harbour swimmable.

Limiting the amount of E. coli carriers contributes to the HHRAP goal of delisting the harbour in a number of ways. The control of geese mitigates damage that could be caused if their population was allowed to expand. Not only does this enhance the area aesthetically and aid in revitalizing water quality, but it also increases the number of days the beaches can be open to the public.

How does it relate to the City of Hamilton's Clean Harbour Program?

Keeping a focus on the water quality of Hamilton Harbour will contribute to the ultimate goal of returning the harbour to a better environmental state. This allows for an ecological balance and clean water.

What is the return-on-investment for the residents of Hamilton?

There are numerous advantages to maintaining Hamilton Harbour’s ecological balance. This directly results in recreational opportunities on the waterfront, tourism through waterfront parkland events, savings in upkeep of the parks and beautiful public spaces.

Public beach at Bayfront Park

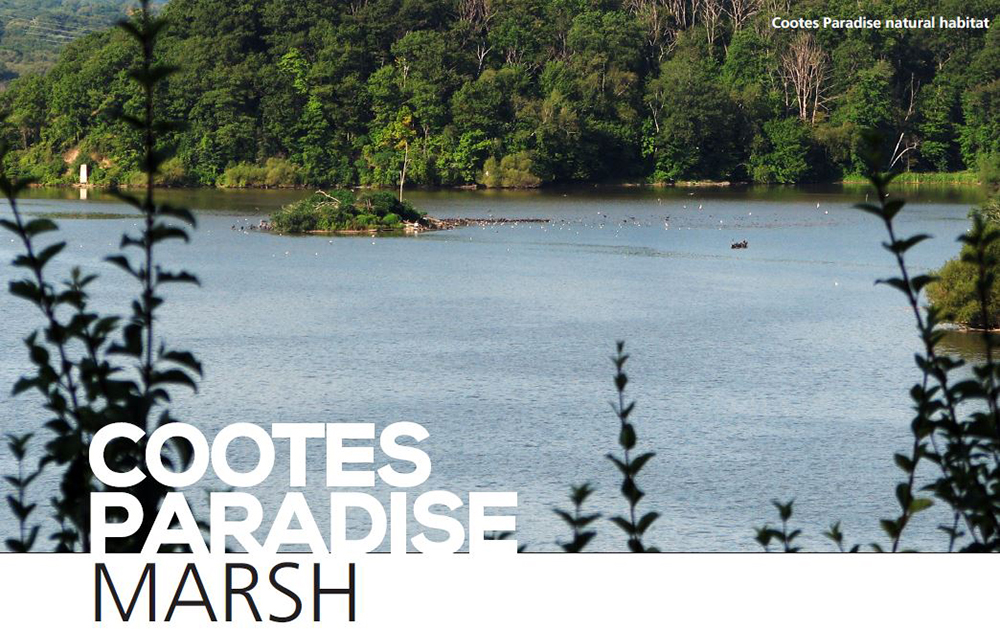

Cootes Paradise marsh is the largest wetland at the western end of Lake Ontario, on the west side of Hamilton Harbour. The wetlands surround old growth forests that support a large variety of plants and animals that include rare and threatened species. The Cootes Paradise nature sanctuary is a magnificent example of plant biodiversity in Canada. In fact, the lands contain one of the highest biodiversity of plants per hectare in Canada and the highest biodiversity of plants in the region with 877 species. It also holds the most endangered species in the region with 35 identified species.

As a result of its location and scale, this wetland is considered to be one of the most important migratory waterfowl staging habitats on the lower Great Lakes and the largest nursery habitat for fish in the region. Cootes Paradise marsh was designated a fish sanctuary in 1874, with the marsh and surrounding lands officially preserved as a formal, provincial game sanctuary in 1927.

Its location makes it an important migratory bird stopover as well. The sanctuary was included as part of the natural land holdings of the Royal Botanical Gardens upon its formation in 1941. Today this 3 km long marsh is the largest fish nursery in western Lake Ontario and one of the most significant migratory bird staging areas on the lower Great Lakes.

Designations to protect Cootes Paradise

This 600-hectare wildlife sanctuary is highlighted by a 320-hectare river-mouth wetland. Owned and managed by the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG), the marsh is part of the Cootes Paradise Nature Reserve. It is designated as a National Historic site, a Nationally Important Bird Area (IBA), and a Nationally Important Reptile and Amphibian Area (IMPARA).

Cootes Paradise wetlands

The Ontario Provincial Government has designated Cootes Paradise as a Provincially Significant Class 1 Wetland and an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI). It also is listed as an Environmentally Sensitive Area (ESA) in the Hamilton Region.

Links to UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve areas

Its urban location makes this sanctuary a vital link to other adjacent Niagara Escarpment UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve areas in the region including Spencer Gorge, Dundas Valley, Iroquois Heights and Borer’s Falls/Rock Chapel. The wetlands 30,000-hectare watershed also acts as the catchment for three main waterways: Spencer Creek (the largest creek in the region), as well as Borer’s Creek and Chedoke Creek. Many smaller streams also drain from the adjacent escarpment, including Delsey Creek, Westdale Creek, Long Valley Brook, Hickory Brook and Highland Creek.

Princess Point rain garden filters storm water

The Princess Point rain garden was installed in 2014 by Bay Area Restoration Council volunteers, in partnership with the Royal Botanical Gardens. Typically, a rain garden is a sunken garden, with deep-rooted native plants and grasses, planted four to eight inches deep, designed to capture, absorb and naturally filter storm water.

During heavy rainfalls and after snow melts, this garden collects storm water from the parking lot and filters pollutants that would otherwise enter Cootes Paradise. Water that enters the garden slowly infiltrates into the ground. The rain garden reduces storm water runoff and downstream erosion which improves water quality. It also provides food and habitat for a variety of butterflies, birds and other wildlife.

Re-planting Cootes Paradise with native species

Related to the goldfish, the common carp is an invasive species that has nearly destroyed plant cover in Cootes Paradise. This is because carp feed along the bottom of the marsh and uproot plants along the way. Surprisingly, it is estimated that carp are responsible for the loss of 85 percent of the plant cover in Cootes Paradise. To counter this effect, the Royal Botanical Gardens Fishway has drastically reduced the number of carp entering the marsh. Another important initiative is the re-vegetation of the marsh. The Bay Area Restoration Council’s Marsh Volunteer Planting Program brings community volunteers into the marsh to assist the RBG with replanting of native species.

Royal Botanical Gardens Fishway

Fishway structure creates carp-barrier

The Royal Botanical Gardens Fishway is probably one of the most well-known sites along the Hamilton Harbour. It is located at the mouth of the Desjardins Canal which is the only channel Royal Botanical Gardens Fishway that connects Cootes Paradise and Hamilton Harbour. The Fishway is the first two-way fishway and carp barrier in the Great Lakes. It began operating in 1997 and is designed to keep non-native carp out of Cootes while maintaining the flow of water and populations of native aquatic species. Before the installation of the Fishway, there were an estimated 70,000 carp in the marsh. As a result of this structure, it is estimated there are less than 1,000 carp in Cootes Paradise.

Learn more about the Cootes Paradies Fishway

Protecting turtles in Cootes Paradise

For a number of years, RBG has worked with the Hamilton Conservation Foundation to protect turtles by installing silt fencing along the length of Cootes Drive. This is because the roadway is directly adjacent to Cootes Paradise Marsh and Spencer Creek which is a major thoroughfare for breeding turtles.

Before installing the fencing, turtles crossing the road were killed regularly as they attempted to reach breeding grounds. The 700 metre silt fence acts as a barrier and guides turtles along the side of the road to culverts where they can pass safely under the road. The turtles are part of the 35 identified endangered species living in Cootes Paradise.

50 years later the bald eagles return

Bald eagles are nearly extinct in the Great Lakes area. But in Cootes Paradise, bald eagles have been wintering and making a slow comeback as a species. The turning point came in 2008 when a pair of bald eagles stayed the entire summer in the sanctuary. This is significant because bald eagles have not nested on the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario in many years. In fact, by the 1980s there were only four active nests in all of the Great Lakes. This amounts to approximately 15 surviving birds. The bald eagle and its survival were greatly affected by a pesticide called DDT, which thins the shells of its eggs compromising the eggs from hatching. For several years, the pair did not lay eggs. Success came on March 22 and 23, 2013, when the first eagles on the Canadian shoreline of Lake Ontario, in more than 50 years, were hatched in Cootes Paradise.

How does it relate to the Clean Harbour Program?

As the result of its proximity on the west side of Hamilton Harbour and the fact that the Dundas Sewage Treatment Plant discharges into the inflowing creeks, Cootes Paradise is positively affected by the Clean Harbour Program. One of the initiatives of the Clean Harbour Program is the installation of Combined Sewage Overflow tanks (CSOs).

Sewer infrastructure is an important and necessary component of any modern city and is fundamental to public health. Across Canada, younger cities have newer infrastructure and dedicated sewer systems. This means that one sewer system is dedicated to handle waste and the other is for storm water.

In the case of older cities like Hamilton, it has both types of systems and much of the downtown has a combined sewer system. This is where a single sewer system collects and handles both the sanitary sewage directly from households and storm water runoff. The City of Hamilton owns and operates one of the largest and most complex combined sewer systems on the Great Lakes and as a result has a number of combined sewer overflows that protect the system against surcharges and overflows during severe wet weather events. In fact, more than 600 km of combined sewers collect both sanitary and storm flows from an area of approximately 52 km. These flows are then directed to the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant for treatment and ultimately released into Hamilton Harbour through the Red Hill Creek.

During dry weather or a light rainfall, flows are conveyed through the combined sewer system before reaching the wastewater treatment plant on Woodward Avenue in the City’s east end.

Royal Ave CSO construction

During a heavy rainstorms, sanitary and storm water inflows exceed the capacity of the system and the treatment plant and may overflow into the natural environment.

To respond to this, the City of Hamilton built a series of combined sewer overflow tanks beginning in the mid-1980s to prevent untreated wastewater from going directly into the 22 local receiving waters in and around Hamilton including Hamilton Harbour.

These “CSO Tanks” hold the untreated wastewater until the Woodward Avenue treatment plant has capacity to treat it, possible several days after a wet weather event. The overflow tanks are also necessary to protect the treatment plant against hydraulic overloading that could upset the sewage treatment processes.

How does it relate to the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan?

Hamilton Harbour is among 43 Areas of Concern (AOC), and one of 17 Canadian AOCs, identified within the Great Lakes Basin by the International Joint Commission (IJC) for Canadian-American Boundary Waters in 1985. The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement requires that Canadian and American governments develop Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) to address pollution problems and restore the beneficial use impairments identified in each AOC. Local governments are also charged with setting out a process for developing these plans.

Beneficial use impairments in Hamilton Harbour and Cootes Paradise, which are at least partially attributable to pollution from CSOs, include restrictions on dredging activities, eutrophication or undesirable algae, beach closings, degradation of aesthetics, added cost to industry for treatment of harbour water, degradation of phytoplankton and zooplankton and loss of fish and wildlife habitat. It is important to emphasize the role of nutrients in this regard and specifically phosphorous as a parameter of concern as a result of its role in the growth of algae.

Setting the goals for the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan

The Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan (HHRAP) Stage 2 Report was completed in November 1992 and subsequently updated in 2002. It is a partnership through numerous stakeholders, including the Federal and Provincial governments Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, and the City of Hamilton (and the former Regional Municipality of Hamilton-Wentworth).

The report presented specific objectives for removing Hamilton Harbour from the list as an area of concern and recommended actions for achieving delisting. The report identified CSOs as a significant source of pollutants. It recommended that Hamilton undertake specific measures to eliminate or minimize pollution from these discharges.

The HHRAP set water quality goals for the Harbour and specific pollutant loading targets (initial and final) to achieve these goals for each of the significant pollutant discharges into Hamilton Harbour, including Hamilton’s CSOs. The HHRAP assigned the elimination or minimization of pollution from CSOs as its first priority and placed the highest priority on CSOs discharging into Cootes Paradise and the West Harbour.

Royal Ave CSO construction

Hamilton's CSO Control Program

Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) are the release of untreated sewage directly into the harbour. CSOs represent a potential hazard and can have adverse affects on aquatic life, recreation uses and water quality. CSOs in Ontario are governed by the Ministry.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks procedures require municipalities with CSOs to prepare Pollution Prevention and Control Plans (PPCPs) that outline the nature, cause and extent of pollution problems, examine CSO control alternatives and propose remedial measures. Municipalities must then recommend an implementation program including costs and schedules.

Hamilton’s original PPCP was completed in 1991 which recommended a number of underground detention storage facilities to capture and temporarily store excess CSO volumes during wet weather. Once the storm had passed, the facilities would then slowly drain and convey their contents to the Woodward Avenue Wastewater Treatment Plant for full treatment during dry weather.

The original PPCP was updated in 2003 and in 2009 as part of the City of Hamilton’s new Integrated Wastewater Servicing Master Plan.

CSO Control Program progress

From 1989 to 2010, Hamilton has constructed nine CSO storage facilities, providing more than 314,000 m3 of total storage volume, which is equivalent to 125 Olympic-size swimming pools, to reduce CSOs to local receiving waters.

The cost to construct all the facilities over the years was approximately $89 million (or $163 million in today’s dollars). As recommended by the HHRAP, the City’s efforts have concentrated on reducing CSOs to Cootes Paradise, the Western Harbour Red Hill Creek and the Eastern Harbour through the construction of CSO tanks.

To reduce the cost of the program to ratepayers, the City of Hamilton sought and obtained funding of more than $20 million from a variety of government programs.

Along with the many upgrades at the Woodward Avenue Wastewater Treatment Plant, the CSO tanks have helped to significantly reduce the amount of raw sewage and surface debris from entering local receiving waters.

This allowed for the re-opening of local beaches, achieved the HHRAP’s initial pollutant loading targets and made significant strides towards meeting HHRAP final targets.

The remaining components of Hamilton’s CSO Control Program include the current implementation of a Construction of Greenhill CSO tank computerized Real Time Control (RTC) system to optimize the operation of the CSS and maximize the volume of CSOs conveyed to and treated by the wastewater plant. This also includes the expansion of the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant to treat more CSOs during wet weather.

Construction of the CSO tanks

The City of Hamilton has successfully reduced the volume of CSOs to receiving waters by half. Currently, this equates to two billion litres of wastewater and storm water not going into receiving waters because of the construction of the numerous CSO storage facilities.

The frequency and magnitude of storms means that receiving waters including Hamilton Harbour, nearby creeks, beaches and other recreational watercourses would be impacted by CSOs every few days. This would mean that the recreational areas would be off-limits for use and would be negatively environmentally impacted.

The first tank, known as HC001 (83,500 m3), or the original Greenhill CSO Tank, was constructed in 1988 at a cost of approximately $5 Million. This tank reduces the frequency and volume of CSOs to Red Hill Creek but was designed and constructed prior to the 2002 provincial guidelines, which stipulates 90% volumetric control of all wet weather flows in an average year.

Construction of Greenhill CSO tank

The first tank did not meet this level of control but did greatly reduce the frequency and volume of CSOs resulting from storms greater than 15mm of rain. This facility was later integrated and improved with a sister facility (HCS06 or Greenhill 2).

HCS02 (21,000 m3) at Bayfront Park was the second CSO tank to be constructed at a cost of $9.3 Million. This tank was completed in 1993 and was designed to reduce the frequency of CSOs to the West Harbour from 13 times a year down to once a year. It also controls more than 90% of the wet weather flow tributary to it.

The construction of this facility has greatly improved water quality and allowed for the West Harbour to be open to the public. Washrooms and an observation platform overlooking the harbour were integrated into this facility.

HCS03 (1400 tank + 1800 inline storage) is known as the James Street CSO tank. This facility was built in 1993 for $1.5 Million and is designed to reduce the frequency of CSOs from 24 times a year to once a year and reduce the volume of CSOs entering the West Harbour at the foot of James Street near the Royal Hamilton Yacht Club and other in-water recreational facilities.

HCS04 is the Main-King CSO tank (approximately 77,000 m3) and was completed in 1997 for $23 Million. This CSO tank is tributary to an environmentally sensitive area known as Cootes Paradise. It is designed to reduce the frequency of CSOs from 29 times a year to 3 times a year and reduce the volume of CSOs. It also controls 90% of the tributary wet weather flow. A park was created above the facility that also contains a cricket pitch and a dog park.

HCS05 is the Eastwood Park CSO tank and was completed in 1997 at a cost of $8.5 Million. It controls CSOs to the eastern-most portion of the West Harbour area and reduces frequency of CSOs from 27 times a year down to two or three times a year. It also controls 90% of wet weather flow.

HCS06 is located adjacent to the original Greenhill CSO tank and was constructed in 2003 at a cost of $16 Million and was designed to work in series with the original Greenhill CSO tank to improve performance at Red Hill Creek and achieve modern performance standards of 90% control.

HCS08 is the Royal Avenue CSO Tank which was constructed in 2007 at a cost of $9M. Its volume is ~ 15,000 m3 and was designed to provide 90% volumetric control of all wet weather flows in an average year for its tributary system to Chedoke Creek and, ultimately, Cootes Paradise.

HCS07 is the Red Hill Superpipe which was constructed between 2004 and 2007 and was coordinated with the massive construction of the Red Hill Creek Expressway. This facility consists of nearly 1.7 km of oversized (2250 and 3000 mm diameter) sewer pipes and provides approximately 15,000 m3 of storage volume.

This facility operates via motorized and remotely controlled sluice gates which retain sewage within the pipe and manholes during a storm.

It then slowly releases this sewage for treatment at the Woodward Avenue WWTP following the storm event. This prevents capacity overloads of the wastewater treatment plant to process and treat the water.

HCS09 is the McMaster CSO tank which was constructed in 2010. It is 5,935 m3 and controls 90% of tributary wet weather flow.

CSO Red Hill Superpipe

Red Hill Valley CSO overflow

How does it relate to the Clean Harbour Program?

The Clean Harbour Program was branded in 2013 and represents a series of projects undertaken by the City of Hamilton aimed at reversing the environmental damage to Hamilton Harbour and in support of the HHRAP.

A number of projects that represent significant investment by the City of Hamilton have been completed over the years in support of the HHRAP and the CSO Control program is foundational in this regard. Hamilton will be revisiting its Water and Wastewater Master Plan with a review of the CSO Control program to explore what further benefits that this very effective program may provide for the future.

What is the return-on-investment for the residents of Hamilton?

The harbour is protected as the series of combined sewer overflow prevents untreated wastewater from going directly into local receiving waters in and around Hamilton including Hamilton Harbour. It’s a sound, environmental solution to protect the harbour from contamination.

The upgrade of the primary clarifiers at the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant began in August 2010. The upgrade was officially complete in April 2013 with the release of the substantial performance certificate. The clarifiers now have the capacity to treat larger wet-weather flows while also producing lower pollutant loading because of the addition of a new chlorine contact chamber for disinfection.

Like every municipal wastewater system, Hamilton’s system has capacity limits imposed by everything from the size of pipes to the speed of treatment processes. Real-time controls help get the most out of the system - whatever its limitations - and maximize the significant investments the community has already made in its water and wastewater infrastructure. With advanced computer software responding to sensors that measure factors such as flow, level, pressure and rainfall, real-time controls manipulate gates, weirs, chambers and pump stations to get the most out of the wastewater system. These responses and adaptations occur immediately, resulting in an overall system that is more capable of managing wet weather flows, better prepared to defend its own systems from damage or overuse and better equipped to protect the water quality of Hamilton Harbour.

The City of Hamilton began its Real-Time Control project in 2008 by identifying approximately $35 million of infrastructure investments required to maximize the wastewater system’s capacity and better position it to meet its goals for everything from localized flood protection to water quality. With funding support from Infrastructure Canada’s Canada Strategic Infrastructure Fund, construction on a number of key systems and upgrades began in 2011 as part of Phase 1.

One of the most significant early milestones of the Real-Time Control project was the installation of a new regulator gate at the Wellington/Burlington Combined Sewer Overflow which was, at the time, the largest uncontrolled overflow in the City. Commissioned in 2012, the regulator gate and control structure have the ability to redirect flow into unused capacity of the Western Sanitary Interceptor North Branch. In the first 10 months of operation, this real-time control capability facilitated the capture of more than 500,000 cubic metres of water that would have otherwise overflowed the system. That improvement, in turn, had a measurable impact on the quality of water being returned to Hamilton Harbour. In just those 10 months, the real-time control at Wellington/Burlington helped prevent 44,500 kg of suspended solids, 120 kg of total phosphorous and 130 kg of ammonium nitrogen from entering the harbour.

In 2022 and into 2023, the program expanded into Phase 2, which included weir heights adjustments and programming changes to retain more wet weather flow within the system with funding support from Infrastructure Canada’s Green Infrastructure Fund.

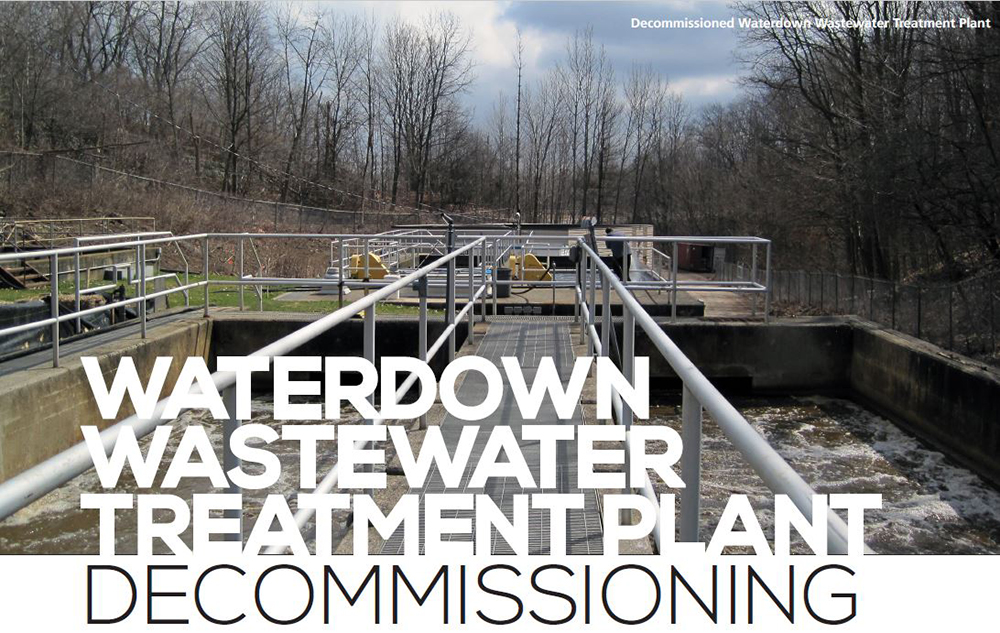

When considering wastewater management, the City of Hamilton takes a pro-active approach to ensure that they are fiscally responsible. With the Waterdown Wastewater Treatment Plant it became apparent that there was a better way to handle the wastewater processing requirements. The decommissioning of the plant began in 2007 and was completed in 2016. With a budget of $8.2 million, the Municipal Class Environmental Assessment Master Water and Wastewater Plan indicated that the preferred alternative was to decommission the plant and replace it with a pumping station.

How does it relate to the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan (HHRAP)?

The primary focus of the HHRAP is to reverse past environmental damage and protect Hamilton Harbour from future damage. The decommissioning of the plant helps to achieve these goals. Effluent wastewater flowed from the Waterdown plant to Grindstone Creek, which is a cold water stream fish habitat that flows to the harbour. It was deemed in the environmental assessment that the water quality would be better for the fish without the wastewater effluent flow. This would, in turn, help the fish in the harbour that spawn in the creek. The decommissioning was the preferred alternative to socially and cost effectively mitigate any further environmental damage. It was also cost-effective to treat wastewater at the Dundas Wastewater Treatment Plant instead of the current Waterdown plant.

How does it relate to the Clean Harbour Program?

The Clean Harbour Program is aimed at reversing the environmental damage to Hamilton Harbour. By developing a more efficient and better environmental way to manage wastewater in Waterdown, this supports the goals of the Program.

Promoting local development

This specific project promotes development in Waterdown as it provides efficient wastewater treatment to the area without affecting local waterways. A pumping station was built to collect sewage flow to be pumped to the Dundas Wastewater Treatment Site. Then a sanitary forcemain and sewer was constructed to connect the pumping station to Borers Creek sanitary sewer interceptor. The flow is then allowed to flow to Dundas Wastewater Treatment Plant or pumped to Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant. This also allows for increased capacity for overflow events by utilizing and converting plant aeration tanks into overflow tanks when needed.

Waterdown North Wetland Trail

What is the return-on-investment for the residents of Hamilton?

The new process in treating wastewater for Waterdown is efficient, cost-effective, and protects our environmental resources.

Started in 2014, the Watershed Nutrient and Sediment Management Advisory Group (WNSMAG) is an on-going initiative, comprised of a senior committee of decision makers that manages the findings of four separate task groups.

The Sediment Control on Active Construction Sites Task Group is focused on reducing sediment and erosion from construction sites through process audits and training.

For the Urban Runoff Task Group, there are two similar task groups based on location. They are the Urban Runoff – Hamilton Task Group and the Urban Runoff – Burlington Task Group. Both are focused on reducing phosphorus and sediment through the expanded implementation of low impact development (LID) techniques, the updating of manuals, stewardship and training.

There’s also a Rural Runoff Task Group with the same deliverables.

How does it relate to the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan (HHRAP)?

The work and findings of the four task groups essentially put the harbour on a “phosphorus and sediment reduced diet” through close monitoring and reporting. This is a positive step as less phosphorus will lead to fewer algae blooms. When you have increased phosphates in water systems, this higher concentration causes increased growth of algae and plants. Algae then tend to grow very quickly when there are a lot of nutrients available in the water. The problem is each alga is short-lived which results in a high concentration of dead organic matter that then starts to decay. This decaying process consumes the dissolved oxygen in the water resulting in hypoxic conditions.

Algae bloom at Desjardins Canal

Without sufficient dissolved oxygen in the water, other plants and animals die off.

Less sediment will lead to less phosphorus as it is frequently attached to sediment particles. In addition, less sediment will also improve water clarity, allowing light to penetrate deeper into the water column. This improves aquatic plant growth and rebalances the fish community. This improves aesthetics for the public visiting the Harbour.

Low impact development (LID) techniques work to infiltrate flows at the source, where the rain falls, thereby reducing flows further down which prevents flooding.

How does it relate to the City of Hamilton's Clean Harbour Program?

In areas with Combined Sewer Overflow tanks, less phosphorus and sediment inputs into the water reduces the pressure on the infrastructure system. Many of the LID techniques will involve a reduction in flows into the water system which again reduce pressure on the infrastructure system as the tanks don’t need to hold this water.

Improving what comes into the harbour from the watersheds will complement the significant investments in infrastructure to combat eutrophication, which is the process by which a body of water becomes enriched in dissolved nutrients such as phosphates.

What is the return-on-investment for the residents of Hamilton?

In doing this work, this provides the residents of Hamilton with healthier creeks as well as improved conditions for Hamilton Harbour and Cootes Paradise marsh. It also provides for a much more pleasant looking environment for the residents to enjoy.

Hamilton’s industrial sector has long dominated the southeast corner of Hamilton Harbour where Windermere Basin has spent decades trapped between industrial lands and the Queen Elizabeth Way, with the Hamilton Beach and Parkview West neighbourhoods nearby. Originally a wetland and mud flat at the mouth of Red Hill Creek, the basin served as a natural filter for the creek water flowing into the harbour and was an important breeding and migratory ground for as many as 26 species of birds.

In the 1950s, however, Windermere Basin was converted into a sediment trap to reduce the need for dredging[3] the areas around Piers 24 and 25. The plan was successful. The basin trapped sediment, but it collected a significant amount of pollution as well.

In 1992, Windermere Basin was identified by the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan as a potential target for rehabilitation and by 1997, the City of Hamilton had begun exploring options. A detailed plan for restoring Windermere Basin was completed in 2005. The bulk of the work took place in 2011 and 2012 and in the years since, nature has taken control of the project. The result is a 13-hectare developing wetland that returns the area to something resembling its pre-industrial ecosystem. A berm separates the basin from the outflow of Red Hill Creek, allowing for improved water quality and habitat regeneration in an area that now includes fish and wildlife habitat along with parkland and a walking trail with access from Eastport Drive. Shortly after the restoration work was complete, the rare black crowned night heron began nesting in the trees surrounding the basin.

With a budget of $20.5 million funded by the City of Hamilton in partnership with the provincial and federal governments, the Windermere Basin restoration was one of North America’s most ambitious wetland restoration projects. This investment provided not only obvious ecological and social benefits, but important economic outcomes as well. Returning the basin to a more natural condition saved millions of dollars in dredging costs. Ultimately, the project transformed an open body of water with limited biodiversity into a healthy and diverse Great Lakes coastal wetland that provides aesthetic appeal, recreation opportunities and natural habitat.

[3] Digging down the bottom of a waterway, usually to create or maintain enough water depth to sustain shipping

Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant Upgrades

The largest investment of the Clean Harbour program was a multi-phase plan to upgrade the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant. Because the plant is the largest single source of water flowing into Hamilton Harbour, the quality of that effluent has a direct and powerful impact on the harbour’s water quality and environmental health. The capital construction cost for the upgrades was approximately $340 million, $200 million of which comes from the provincial and federal governments through the Green Infrastructure Fund.

The upgrades include elevating the plant’s final treatment process from the secondary level to the tertiary (third) level. This allows the plant to reach strict discharge limits described by the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan for phosphorus, ammonia and suspended solids.

At $340 million, the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant upgrades represent the largest investment within the City of Hamilton’s Clean Harbour Program. The upgrade project was a multi-phase, multi-year process that included a number of sub-projects, each of which had its own specification and timelines.

In 2008, the City completed the Woodward Avenue WWTP Service Area Schedule 'C' Environmental Study Report to determine a plan for upgrades to the Woodward WWTP to manage wet weather flows, provide treatment capacity, and meet treatment objectives defined by the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan, the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks and the Federal Environmental Protection Act.

Past update videos: Fall 2018 | Fall 2019 | Fall 2020 | Summer 2021 | Fall 2021

In October 2022, a crucial milestone was achieved as the secondary effluent started to flow through the Tertiary Treatment Facility, simultaneously initiating the commissioning period. This achievement signifies a momentous step towards transforming the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant from a secondary to a tertiary level treatment facility. Meeting this goal reflects the City's commitment to fulfilling the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan Targets.

The Tertiary Treatment Upgrades project officially reached Substantial Performance on April 15, 2024 and transitioned to the 2-year warranty period.

As of August 31, 2024, the 2-year warranty period for the Main Pumping Station has ended. Final tasks to achieve Final Completion of the contract are being addressed.

As of November 11, 2024, the 2-year warranty period for the Electrical Power Upgrades has ended. Final tasks to achieve Final Completion of the contract are being addressed.

While there are significant environmental, economic, and aesthetic benefits associated with the completion of this project, the City understands the importance of maintaining ongoing communication with residents and ensuring the project and associated impacts are compatible with the community.

If you are interested in becoming a member of the Community Liaison Committee during future phases, or if you wish to receive additional information regarding the Community Liaison Committee, please refer to the contact information provided below.

CLC Information Contact

905-546-2489

[email protected]

Odour Concerns

Process Supervisor

905-546-2424 ext.1086

General Inquiries, Noise, Dust and Traffic Concerns

Hamilton Water - Customer Service

905-546-2489

Reference: WOODWARD CONSTRUCTION