Current Clean Harbour Projects

Watershed Action Plan

Learn about the actions to help delist Hamilton Harbour as an Area of Concern.

The Clean Harbour program is a series of projects designed to have a direct impact on the health of our local environment, specifically the water quality of Hamilton Harbour. When the International Joint Commission delists the harbour as an area of concern (AOC), these projects will have played a significant role in achieving that community milestone.

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project

The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation project addresses the largest toxic sediment site in Canada by building an engineered containment facility (ECF) that will isolate the contaminated material from the harbour ecosystem. A long preparation and planning period has now given way to a full-speed-ahead construction phase that is expected to continue until 2026. The City of Hamilton is one of seven funding partners participating in the project under the leadership of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

The City of Hamilton has committed $14 million of the $140 million project budget. With funding from four levels of government as well as institutional and corporate partners, the Randle Reef ECF will be an outstanding example of the partner approach that is so much a part of the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan.

Once completed, stewardship of the ECF will transfer to the Hamilton-Oshawa Port Authority which will use the facility as a new port space to support the shipping industry in Hamilton Harbour.

Navigate to the Randle Reef tab for more information.

Cross-Connection Control Project

The Cross-Connection Control project involves a series of initiatives designed to locate and eliminate crossed sewer pipes that are discharging sewage into the City of Hamilton’s storm sewer system, thus allowing that sewage to enter the harbour untreated.

A pilot project that involved sampling sewer outfalls, inspecting storm sewers, homeowner engagement, dye tests, engineering investigations, inspecting sewer laterals (the pipe connecting the sewer main to an individual home) and the uncrossing of a number of pipes, helped define the kind of process required to expand the program across the City. As the City of Hamilton works with homeowners and business owners to correct a growing number of cross connections, it will reduce the amount of untreated sewage being discharged into the harbour and thus help meet HHRAP water quality targets.

City of Hamilton Watershed Action Plan

The City of Hamilton has taken steps to develop a comprehensive Watershed Action Plan and reiterating its commitment to the water quality objectives outlined in the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan. The new Watershed Action Plan identifies and guides the work to address non-point-source contamination and focuses on activities that are within the care and control of the City of Hamilton. Actions under the new Watershed Action Plan will benefit recreation and natural habitats in the watershed and continue the process to delist Hamilton Harbour as an identified Area of Concern.

Projects in the Pipeline

As Hamilton’s Clean Harbour program progresses on its current projects, it continues to evaluate and plan for the future. This includes initiating new projects and connecting with related undertakings throughout the Hamilton Harbour watershed. Anticipating work includes:

- Dundas Wastewater Treatment Plant Upgrades: The upgrades to the treatment plant includes a major infrastructure replacement project that includes enhanced tertiary treatment. In total, the Dundas Wastewater Treatment Plant project will require an estimated $252 million investment.

[1] The Desjardins Canal, which opened in 1837 and was effectively out of use three decades later, allowed ships to pass through Burlington Heights ay the west end of Hamilton Harbour and go through Cootes Paradise (which was a marsh at the time) to reach the town of Dundas

When the first Europeans arrived in what would become Hamilton, Cootes Paradise was a dense 250-hectare marsh and one of the most important fish nurseries and migratory bird staging areas on the Great Lakes. As communities grew around Cootes Paradise, however, urban and rural runoff began to erode water quality. The shipping-related control of water levels in Lake Ontario also had a negative impact on Cootes Paradise, as did invasive[1] fish species, chief among them, carp.

Fast-growing carp were introduced to Hamilton Harbour in the late 1800s to enrich local commercial fisheries. By the 1930s, this non-native species with its bottom-feeding and spawning activities had begun uprooting and crushing aquatic plants in Cootes Paradise while also stirring up sediment and creating less-than-ideal conditions for aquatic vegetation.

By the 1980s, almost none of the original Cootes Paradise wetland remained. Fish and bird habitat had been replaced by turbid[2] open water. It was clear that, among other changes, carp needed to be kept out of Cootes.

Grindstone Creek, the first entrance for carp, was closed with a simple but inventive Christmas tree barrier. Made from hundreds of trees, the barrier allows for the movement of water and small fish, but excludes adult carp.

The second carp doorway to Cootes required a higher-technology solution. The Cootes Paradise Fishway opened in 1997 at the mouth of the Desjardins Canal. The first two-way fish barrier on the Great Lakes, the Fishway keeps destructive carp out of the fragile marsh while allowing smaller native species to move naturally. Since the opening of the Fishway, the Cootes Paradise carp population has dropped by 95%, from approximately 70,000 to less than 1,000 adults.

The exclusion of carp has allowed the marsh to begin its recovery. Native species are being replanted every year. This, in turn, recreates fish, bird and amphibian habitat. The signature moment of the restoration process was the return of bald eagles to Cootes in 2008 and, in 2013, the first hatched eaglets on the Canadian shoreline of Lake Ontario in more than half a century.

The Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG) manages the Fishway which was a joint project supported by the RBG, the City of Hamilton, the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, ArcelorMittal Dofasco, the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan office, the Bay Area Restoration Council, the City of Burlington and private donors.

[1] Any plant or animal that is not naturally occurring in a specific area is “invasive” and can cause problems in the ecosystem because – most frequently – it is not properly balanced by other species that eat it

[2] Muddy and dense with various suspended particles

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are bad for you. More than 695,000 cubic metres – about the volume of three professional hockey arenas – of PAH are bad for an entire ecosystem. That’s how much toxic sediment sits on the floor of Hamilton Harbour on the south shore, approximately between Wentworth Street North and Birch Avenue. This is the Randle Reef toxic sediment site. The worst deposit of its kind in Canada, it is the unfortunate legacy of more than a century and a half of varied industrial activity in the area. It is also one of the major obstacles the community must address before Hamilton Harbour can be considered for delisting as an area of concern.

Addressing Randle Reef has been a Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan priority since 1992 when a four-year study investigated different strategies for removing, containing or destroying the toxic sludge. In 2002, an Environment Canada-led Project Advisory Group provided consensus support to a plan that would leave the dangerous sediment in place but capture it in an engineered containment facility (ECF). The preliminary design for the ECF was completed in 2006, laying the groundwork for detailed design, financial planning, partnership arrangements and other key project elements. In 2013, the Randle Reef project partners completed the necessary legal and funding agreements and after more than two decades of work, the Randle Reef sediment remediation[4] project finally had a full green light.

A tremendous example of a partnership that involves multiple governments and corporate partners, the funding for the $140 million Randle Reef ECF is provided by the Government of Canada, the Province of Ontario, the City of Hamilton, U.S. Steel Canada, the Hamilton Port Authority, the City of Burlington and Halton Region.

Construction began in 2015 with an expected completion date of 2026. At that time, the Hamilton Port Authority will accept ownership of the 6.2 hectare ECF and begin operating the site as a port facility. With double steel-sheet pile walls driven to depths of up to 24 metres into the harbour floor, inner and outer walls and a multi-layered cap, the ECF is being built to specifications that will ensure it has a 200-year lifespan.

[4] Acting of fixing something that has been damaged

Not far from the southeast corner of Hamilton Harbour, in the shadow of the Queen Elizabeth Way, there is a National Historic Site at 900 Woodward Avenue. Now welcoming visitors as the award-winning Hamilton Museum of Steam & Technology, the fully restored Victorian facility is a working monument to one of the most important milestones in Hamilton’s development as a major urban centre.

In 1832 and again in 1854, Hamilton suffered major cholera epidemics. A virulent and deadly bacterial disease most often caused by ineffective sewage practices and unclean drinking water, these outbreaks provided strong motivation for civic leaders to begin planning the City’s first community waterworks. The initial detailed proposal was developed in 1836, but it wasn’t until 1854 when the city ran a contest to select the best design. Thomas Coltrin Keefer was the winning architect.

Construction began in 1856. The mission of the waterworks was simple and important: to deliver large quantities of clean water for safe drinking and for fire control throughout the rapidly expanding City. Hamilton turned on the massive steam-powered Gartshore pumps – examples of some of the most advanced technology of the day – in 1859. Over the years, the original facility expanded to include a second steam-powered pumping station (1887) and a third pumping station driven by both electric and steam power (1913).

The waterworks remained in operation until 1970 when it was replaced by a new facility nearby. By that time, the original waterworks had grown into something of a campus with multiple buildings of varying qualities and permanence. Today, the 1859 Pumphouse remains with its engines and equipment intact. The Boilerhouse, Chimney and Woodshed also survive from 1859, as do three other historic structures: the Worthington Shed (1910) containing a small steam pump, a second Pumphouse (1913) and a Carpenter’s Shed (1915).

Declared a National Historic Site in 1997, the Hamilton Museum of Steam & Technology preserves two 70-ton steam engines, perhaps the oldest surviving Canadian-built engines, and offers visitors a rare and immersive opportunity to experience the way industrial technology helped improve the quality of life in Hamilton, making the City a far safer and healthier place to live.

The Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan (HHRAP) describes a list of “beneficial use impairments” (BUI) that have put Hamilton Harbour on the International Joint Commission’s roster of areas of concern (AOC) on the Great Lakes. The BUIs relate primarily to fish and wildlife (including loss of habitat, the presence of undesirable algae and fish/wildlife illness) and to human interaction with the harbour (including obstacles to swimming, recreational uses and drinking water quality).

The challenge of reducing or even fixing the BUIs is that each is a multifaceted issue. For example, solving many BUIs requires improvements in harbour water quality. Improving water quality requires enhancements in water treatment plants; better management of industrial, institutional and household waste and runoff; potential changes to agricultural and construction practices; more effective stewardship of the watershed[5] that feeds into the harbour; policy controls that influence land use and development; investments in better storm water management; effective water quality testing programs and enhanced public education, to name just a few of the issues at play.

The HHRAP identifies the necessary interim steps and points of progression required to build toward the day when each BUI is taken off the to-do list. The HHRAP also identifies the community partners that are best positioned to address each aspect of the plan’s goals.

The Remedial Action Plan was prepared in 1992 after extensive community consultation. In the simplest terms, the plan works to manage or solve the legacy of ecological degradation in Hamilton Harbour and its watershed while also working to limit future damage. The plan acknowledges that given the economic and recreational importance of the harbour, it will never return to a pristine natural state. Instead, the goal of the HHRAP is to create a healthy, sustainable multi-use harbour that will be able to play many roles in the life of the local community.

The HHRAP addresses its desired outcomes in three stages. The first stage is an assessment of the environmental conditions and a definition of the specific problems. The second stage provides a list of goals, options and recommendations on how to improve on that starting point. The final stage addresses strategies for evaluating progress and ways to confirm that the goals of the HHRAP have been met.

[5] The geographic area in which all creeks, streams and rivers eventually drain into the same body of water, in this case, Hamilton Harbour

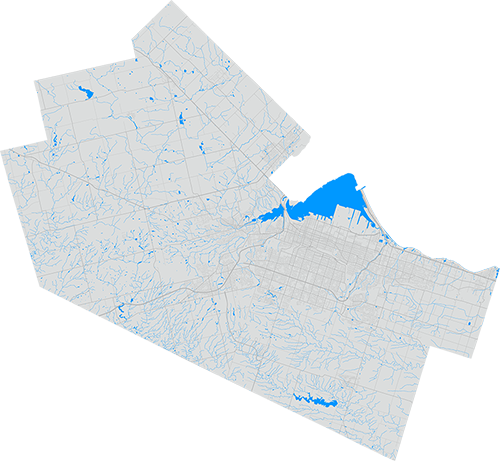

What is a watershed? A watershed is an area of land drained by a river or creek and its tributaries into a body of water like a lake, ocean or harbour.

What is a watershed action plan? It is a framework to guide our decisions and actions to protect, restore and enhance natural resources to support healthy and resilient communities.

Watershed action plans require regular review. As we face new challenges, access new science and technology tools, we can better assess the impact of changing landscapes on watershed health and determine relevant actions and responses.

How will the watershed action plan be funded?

Currently, the City primarily funds its stormwater management program through its water and wastewater utility revenues. That means that properties contribute to stormwater management and the required infrastructure based on the amount of drinking water that is consumed. The City is investigating the viability of implementing a more equitable stormwater funding model. This will ensure the City adheres to Ontario Regulation 588/17: Asset Management Planning for Municipal Infrastructure, which requires municipalities to have sustainable funding mechanisms for key assets. This new sustainable funding mechanism will help support the implementation of the watershed action plan.

About the City of Hamilton’s Watershed Action Plan

Many years of work and investment have been put into reducing point source contamination into Hamilton Harbour and by the end of 2023, the majority of this work will be implemented. This shifts the primary harbour impact to non-point watershed sources. In order to continue progress toward improved harbour conditions, a collaborative effort is required to plan, develop and execute watershed actions within the care and control of the City of Hamilton.

To meet the expectations for an improved aquatic environment, address community expectations, and continue to improve the City’s image for effective environmental stewardship, the City has assembled a consortium of agencies, under a Liaison Committee, to develop the City of Hamilton Watershed Action Plan (CHWAP). Working together, this group of agencies will help to advance City specific non-point watershed actions having the greatest influence on improving harbour conditions to support the eventual delisting of Hamilton Harbour as an Area of Concern.

Liaison Committee membership is structured to provide a balance of perspectives, skills sets, knowledge and expertise and may include, but is not limited to, the representation shown below. Guests will also be invited to participate in meetings by providing insight, submitting findings and offering additional support depending on agenda items.

The CHWAP Liaison Committee includes:

- City of Hamilton Staff from

- Public Works

- Hamilton Water

- Environmental Services

- Transportation Operations & Maintenance

- Planning & Economic Development

- Sustainable Communities

- Heritage and Urban Design

- Growth Management

- Climate Change Initiatives

- Healthy & Safe Communities

- Recreation

- Indigenous Relations

- Public Works

- Hamilton Conservation Authority

- Conservation Halton

- Royal Botanical Gardens

- Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority

- Grand River Conservation Authority

Additional consultation and engagement partners, listed below, will also provide insight, recommendations and additional support to the CHWAP Liaison Committee.

- Bay Area Restoration Council

- City of Burlington

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Environment Hamilton

- Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan

- Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

- The Regional Municipality of Halton

- Indigenous Nations and First Peoples

- Grand River Conservation Authority

- McMaster University

- Redeemer College University

- Green Venture

- Ontario Ministry of Transportation

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Public Engagement

- Recording of Watershed Action Plan virtual public meeting held August 20, 2024

- Recording of Watershed Action Plan virtual public meeting held May 2, 2024

- Watershed Action Plan Public Engagement

Contact

Tim Crowley

Senior Project Manager – Watershed Management

Public Works, Hamilton Water

Email: [email protected]

Call: 905-546-2424 Ext.5063